The Meaning of Things

PROFILE

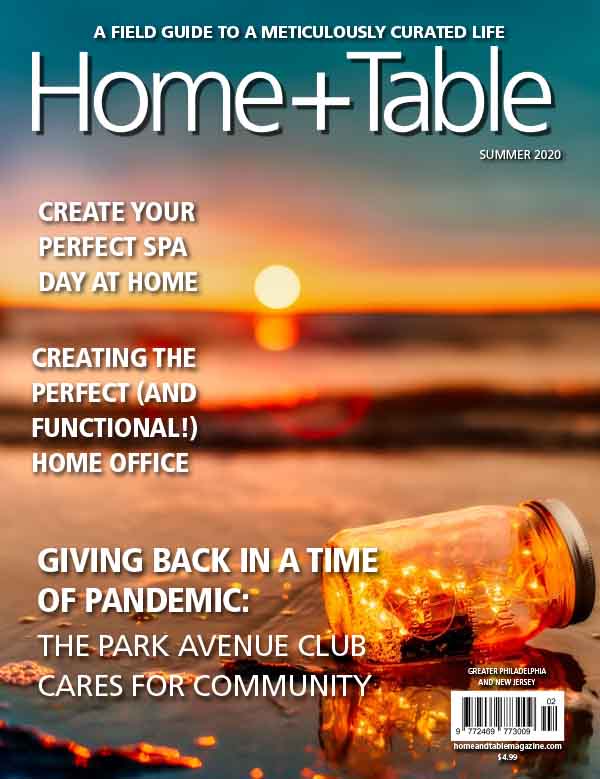

The way that those handsome Billykirk bags only seem to get better with age, that’s not by accident. That’s the sweet spot that Chris Bray, one of the two brothers behind the brand, has been chasing after his entire life. Here, he invites us into his New Hope home for a glimpse of his countless points of inspiration.

By Scott Edwards

Photography by Josh DeHonney

Bray, pictured with his family at their New Hope home. Above and below, some of his collections.

The large rooms and modest décor give the 18th-century New Hope home a lived-in, English manor feel. Chris and Tracy Bray moved their young family here from Jersey City, New Jersey, a few years back for the schools and, as Chris describes it, a “little bit of land.”

In the tiny plot behind their brownstone, he managed to nurture a rather robust garden. “I had plants that had, like, 250 different habaneros,” he says. And, “I was probably one of the only people that had chickens in my backyard.” Also safe to say: His rooster was not popular around his block.

Chris has spent almost all of his adult life in major northern and western cities, but he exudes an easy charm that stems from his Tennessee roots. He’s animated at turns, but he’s never rushing. A formal interview with him almost immediately becomes an organic conversation.

He and his brother, Kirk, founded the leather and canvas goods company Billykirk 17 years ago in Los Angeles. A little over a decade ago, they moved it east. And today, they maintain a studio in Jersey City, a flagship store in Lower Manhattan and a presence in fashionable boutiques around the world. This month, they’re launching a new line with J.Crew, a longtime partner. Billykirk is a brand that’s become synonymous with boundless utility, old-school craftsmanship and aging handsomely. And in those same ways, it’s also become a pure extension of Chris.

Losing ground

“This, right here, was found in our backyard in Jersey City,” Chris says, as he deposits the object in question in my cupped hands.

Is this a cannonball?

“Yeah. That’s Revolutionary War right there,” he says.

It weighs 12 pounds, but it feels heavier. Chris consulted a historian who told him that Communipaw Cove, which no longer exists, teemed with British gunboats during the war, and their yard was well within the range of their canons.

“He said there’s a good chance that it hit our backyard and it stayed there until now, because it was deep,” Chris says. “He also said, when they were leveling out the land, there’s a chance that it was dug up and planted there. I like the first story.”

He restores the cannonball to the mantel over a large fireplace in the more formal of two living rooms. Chris is a guy consumed with stuff, but not in the manner of a collector, nor in the way of a hoarder. He’s more of a historian, because it’s the stories that he connects with. The objects, whose value he cares little about, not that there’s much of it in most cases, are merely remnants and physical cues.

He used to be much worse. Tracy’s reined him in. A personal trainer with an online supplement program called Leany Greeny in development, she shares little of his fascination with artifacts. Moving cross-country has a way of doing that. And as a Briton, she’s done that and then some.

“When she first met me, she thought I lived with my grandfather because I had pipes and smoking stands,” Chris says.

There’s still some evidence of his collections scattered around the house—the cannonball, a candid portrait of Marilyn Monroe that was taken and given to him by the revered photographer William Woodfield, whom Chris befriended toward the end of his life in LA—but most of what remains has been relegated to his third-floor office and his workshop in the basement, where he crafts small sculptures with various found objects. So we head upstairs first.

On a wall outside of his small office that faces the third-floor landing, Chris has arranged a stylish vignette that could hold down the display window at the Billykirk flagship. It’s comprised of some of his oldest Billykirk possessions—a well-worn, black watchstrap that dates back to the company’s inception, a hand-stitched leather satchel inspired by a World War II-era Belgian map bag—and some of his most prized personal ones—swatches of olive drab canvas from his uncle’s Vietnam boot bag, a Swiss medic case.

Inside the office, beside a spare desk and an old lamp and chair, there’s an enclosed, built-in closest and a slim dresser that sits between them. The closet and the dresser are crammed with loose ends.

“These are my dad’s boots … Just an old switchblade, came out of my neighbor’s place. He passed away. Again, they were throwing everything out in that house,” Chris says, taking partial inventory of the dresser’s contents.

I spot a pair of Dorothy-looking, red-sequined girls shoes in a corner. “My daughter went through a couple pairs of these,” he says. “I just kept them because she beat the hell out of them, and I just liked that.”

Earlier, in the course of a conversation that intertwined references of this stuff with his and Kirk’s ambition to turn Billykirk’s bags, belts and cardholders into the kinds of possessions that get passed down, I asked, finally, where this obsession with heirlooms comes from.

“My family’s an old, old American family,” he says. The Daniel Bray Highway, that stretch of Route 29 that runs between Stockton, NJ, and Frenchtown, NJ, it was named after a relative. “When that happens, you’ve got just this huge family that, by and large, most of them kept stuff. We keep stuff. We pass stuff down. The connection we have with stuff, it’s just important. For me, it’s just important.”

“My family’s an old, old American family,” he says. The Daniel Bray Highway, that stretch of Route 29 that runs between Stockton, NJ, and Frenchtown, NJ, it was named after a relative. “When that happens, you’ve got just this huge family that, by and large, most of them kept stuff. We keep stuff. We pass stuff down. The connection we have with stuff, it’s just important. For me, it’s just important.”

And yet, even standing among these crowded shelves and drawers, the stuff’s not as important as it once was. Since Tracy’s intervention, Chris describes himself as “sort of a minimalist.”

“I’m not gonna kill myself trying to save any of it. I just won’t. At the end of the day, I’ve sort of realized it’s just stuff,” he says. “I mean, my wife really kind of helps me remember that.”

Do your daughters (Matilda, 11, and Willa, 6) have any interest in it?

“Yeah. You know, there’s something,” Chris says. “They want to go through my junk drawers. They’re not ready, because they’ll lose stuff.”

So there’s still some value to him, more than he’s likely admitting here, considering the ease with which the stories come and the degrees to which he lights up telling them. Matilda and Willa are curious kids, even though they hardly act their ages. Matilda’s working with a former Bucks County Poet Laureate to publish her first book of poetry. And Willa, “She’s a piece of work,” Chris says. “Fiercely independent.” It’s inevitable that some of his sentimentality is likely to rub off on them, but Matilda and Willa appear to be firmly entrenched on Team Tracy.

A beautiful mind

The sculpture, Chris has been doing for a while now, “getting my mind off stuff.” From the third floor, we’ve descended many steps to reach a cave-like room in a corner of the short but sprawling basement. Chris’s collections have migrated, literally, to the extreme reaches of the home.

Relatively organized clusters of found objects are scattered across a workbench just inside the doorway. Within arm’s reach, there’s a small table, atop which sit several assembled pieces, all about the size of a fist.

“I’m just making shapes here,” he says. “Here’s a piece I just did. That’s a frog gig. This is part of a wooden loom.”

Chris retreats to the other side of the room—in order to do so, he shimmies around a massive, old nautilus machine that occupies at least two-thirds of the floor space in this room—to retrieve a weathered lobster buoy so that he can assemble a loose mock-up of a lamp he plans to create. I’m cynical until it comes together. There’s an unlikely cohesiveness in his creations, even the lobster buoy lamp.

He also powdercoats everything and anything that looks like it would be improved by being powdercoated. He picks up a little iron weight plate. “I like olive. So I powdercoated this little weight olive,” he says. “It takes sort of a weird brain to go for it. That’s sort of what makes me tick.”

You can find Billykirk (@billykirkinc) locally at The Selvedge Yard in New Hope, Modern Love in Frenchtown and Art in the Age in Old City.